In the Eastern Mediterranean, there remains to this day an artifact of one of the most extraordinary military sieges in history. In his siege of Tyre in 332 BC, Alexander the Great of Macedonia undertook one of the most unusual and impressive construction projects of the ancient world which permanently altered the Mediterranean coastline.

Alexander’s siege of Tyre is remarkable in its own right, but even more astounding is that it was foretold with startling accuracy and detail by the Biblical prophet Ezekiel hundreds of years before it took place. As a fan of history, I had read about the bizarre and fascinating details of this battle long before I was aware there was a Biblical prophecy surrounding the event. When I came across Ezekiel’s foretelling of Tyre’s destruction (Ezekiel chapter 26)[1] in the exact manner in which it eventually happened, I was stunned. This led me on a lengthy investigation of the historical account of the fall of Tyre, and ultimately why I wrote this piece.

ANCIENT TYRE

Tyre was an ancient Phoenician city-state situated on the Mediterranean coast. By the time Ezekiel was writing this prophecy (6th century BC), the Phoenicians had developed an extensive maritime trade network and established themselves as the dominant commercial power of the known world. Because of its geographical position and sheltered harbors, Tyre was at the forefront of this trade network and became one of the wealthiest and most influential cities in history, not to mention the cultural and cosmopolitan center of the Ancient Near East.

The city consisted of two parts[2-9]: the political and commercial center situated on an island just off the coast of modern-day Lebanon, and the population center located about a kilometer opposite on the coast of the mainland.[10,8] The mainland sector of the city was called by the Greeks Paleotyre (Old Tyre). Beyond the urban center on the mainland, Tyre also controlled the surrounding fertile plain (an area of about 15 miles) comprised of minor towns, villages, and farms[8,11,12] (these outlying settlements of a larger city are often referred to as “daughters” or “daughter villages” throughout the Bible).[13-18]

GOD’S PROCLAMATION AGAINST TYRE – EZEKIEL 26

Early in the 6th century BC, the Babylonians conquered and destroyed the city of Jerusalem and deported the Jewish people to Babylon where they were held captive for the next several decades. It is during this time period, known in Jewish history as the “Babylonian captivity,” that God pronounced the coming destruction of Tyre through the prophet Ezekiel.[19] When news of Jerusalem’s fall reached the people of Tyre, they gloated over the demise of their regional neighbor, prompting the Lord’s judgment (Ezek. 26:2).

There are several aspects of this prophecy that warrant close attention and scrutiny:

- God will cause many nations to come against Tyre, as the sea causes its waves to come up (verse 3)

- Tyre’s daughter villages will be slayed by the sword (verse 6, 8)

- The city’s stones, timber, and soil will be thrown into the water (verse 12)

- Tyre’s dust shall be scraped from her, she will be made “like the top of a rock” (verse 4, 14)

- The invaders will plunder Tyre’s riches (verse 5, 12)

- Tyre will become a place for spreading nets (verse 5, 14)

- Tyre will never be rebuilt (verse 14)

Only a short time after its revelation to Ezekiel, the prophecy was seemingly fulfilled when those same Babylonians, led by king Nebuchadnezzar, marched on Tyre and besieged the city in ~586 BC. Nebuchadnezzar’s armies devastated Tyre’s mainland presence; they slaughtered Tyre’s coastal farming suburbs and outlying settlements (Tyre’s “daughter villages”)[13-18] and laid siege to Old Tyre, which eventually fell and was destroyed, but not before many of the inhabitants took the city’s riches and fled to the relative safety of the island.[3,6,8,9,12]

As for the island, Nebuchadnezzar’s siege lasted another 13 years until the Tyrians finally surrendered.[20] The details of the defeat aren’t known, as there are precious few sources available to us today concerning the event. In all likelihood the Babylonians simply cut off the island from resupply, starving the Tyrians into eventual submission.[20,12] Regardless of what may have happened, it’s clear that the island-city was not taken by force and utterly demolished as predicted by Ezekiel.

A FAILED PROPHECY?

Here is where we enter the crux of the debate and confusion surrounding Ezekiel 26. At a cursory glance, it seems that this entire passage (chapter 26) deals exclusively with Nebuchadnezzar’s assault on Tyre. In other words, everything that Ezekiel mentions will befall Tyre – from its pillaging to its total and final destruction – would come at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar. We’ve already seen that Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the mainland sector of Tyre but left the island portion intact, so it would seem that Ezekiel quite frankly was wrong. Many critics hold this view; in their eyes, this is a “failed prophecy,” which Ezekiel later acknowledges in 29:17-20. But is this the correct way to read this passage – that Nebuchadnezzar would be the one and only agent of destruction?

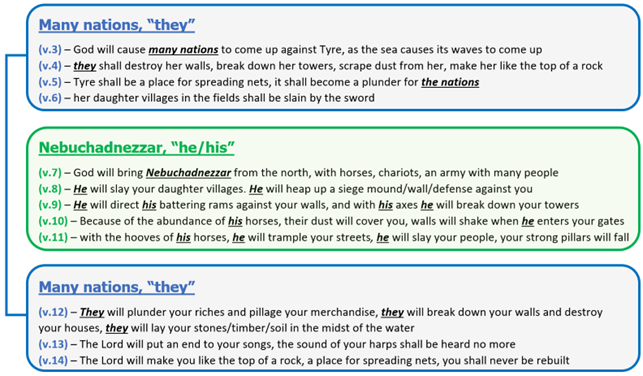

Scholars have long noted the pronoun change between the plural “they” and the singular “he” throughout verses 3-14. This may seem immaterial at first, but after digging into the text a little further it becomes clear that this is more than just an arbitrary choice of words by the author. A careful examination of the passage reveals a three-part structure.[21]

The first section (v.3-6) explains how the LORD will bring many nations (“they”) against Tyre, “as the sea causes it’s waves to come up.” This “waves of the sea” metaphor is significant, as it gives the reader a sense of the relentless and episodic nature of the coming invasions. Ezekiel paints a picture of nation after nation coming against Tyre like one wave after another crashing against the shore.[21]

The second section (v.7-11) then spotlights one episode in this series of invasions – one “wave” if you will – focusing on the Babylonians led by Nebuchadnezzar.[21] Verses 7-11 describe how Nebuchadnezzar, repeatedly denoted by “he” and “his,” will slay Tyre’s daughter villages and then besiege and destroy the city, knocking down its walls and towers.

In the third section (v.12-14), we see the pronouns “he” and “his” abruptly shift back to “they,” indicating that Ezekiel is no longer referring specifically to Nebuchadnezzar but has reverted to talking about the actions of the many nations (“they”) that will continue to assault Tyre. This section parallels the first section and repeats what is said in verses 3-6, adding that Tyre’s stones, timber, and soil will be thrown into the water, and that Tyre will never be rebuilt.[21]

Considering this, we can grasp what Ezekiel is saying: many different nations will attack Tyre, one after another in continuous succession like a set of waves crashing against the shore. The Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar would merely be one of the “many nations” to invade Tyre. Nebuchadnezzar’s armies would be responsible for some of the destructive events that Tyre would suffer, but not all.*

More specifically, Nebuchadnezzar would kill Tyre’s people and cause some destruction, but would neither completely annihilate Tyre nor plunder its riches.[21] This actually aligns perfectly well with Ezekiel 29:17-20, rather than contradicting it as many have claimed.[21]

*This is evidenced further by the fact that certain actions mentioned in the many nations (“they”) sections – stones laid into the water, plundering of riches, total & final destruction – are conspicuously absent from the Nebuchadnezzar section (2nd section), whereas the actions attributed to Nebuchadnezzar in the 2nd section are indeed repeated in the all-encompassing many nations (“they”) sections.

STILL A FAILED PROPHECY?

Even with the understanding of the literary structure and devices used by Ezekiel in this passage, the fact remains that Nebuchadnezzar never assaulted the island-city. Because the island was where Tyre’s commercial, religious, and administrative activity was concentrated, many skeptics question whether an attack on the mainland alone can truly be considered an attack on “Tyre.” Some even insist that the mainland city is not Tyre at all and should be seen as a separate settlement entirely! They use this argument to yet again declare this to be a failed prophecy. Let’s examine this further.

The prevailing view among historians is that the city on the mainland was the original settlement, and shortly thereafter the inhabitants expanded to and colonized the island.[3,6-9] But regardless of their specific origins, these two small settlements soon jointly grew to become the great and influential city-state known to history as Tyre. In ancient Assyrian and Egyptian texts, the original mainland settlement is referred to as “Ushu,” which is merely an earlier name for Melqart, the Phoenician god of Tyre.[3] From this we can plainly see the connection between the ancient settlement of Ushu and the later city-state of Tyre. When the Greeks arrived on the scene many centuries later (at the start of the classical era), they referred to this mainland settlement simply as Old Tyre (Paleo-Tyre). The reason for this is simple: by this time, both the island and mainland settlements had long since become two parts of the same greater city. Both settlements were equally considered, and, collectively known as, Tyre. Scholars overwhelmingly support this claim.[2-9]

Even Antonia Ciasca in the definitive four-part study of the Phoenicians written under the direction of the distinguished Sabatino Moscati, professor at Sapienza (the premier university in the world for Classical Studies and Ancient History)[22,23] and president of the Institution for Phoenician and Punic Civilizations[24] (now the ISMA), unambiguously refers to the mainland settlement that Nebuchadnezzar destroyed as “the mainland sector of the city of Tyre.”[25]

As if this weren’t convincing enough, perhaps the best way to argue this point is to allow the Old Testament’s usage of the word “Tyre” determine its meaning and definition.[26] Rather than relying on our present-day conceptualization of Tyre, which is thousands of years removed from the historical and cultural context in which the Hebrew scriptures were written, let’s let the text speak for itself.

The earliest mention of Tyre in the Tanakh (Old Testament) is in the book of Joshua (Jos. 19:29) where it is named among the places on the border of the tribe of Asher whose territory extended to “the fortified city of Tyre,” which can be none other than the mainland settlement.[27,29-33] Tyre is then mentioned again in 2 Samuel 24:7 in the same manner: as a fortified mainland city.[27,28,34,35] Additionally, there are numerous references throughout the Old Testament to king Hiram of Tyre sending cedar wood along with engineers to Jerusalem for construction projects (2 Samuel 5:11, 1 Kings 9:11, etc.). These cedar trees famously grew on the mainland of modern-day Lebanon (hence the emblem on Lebanon’s flag),[36,37] demonstrating that Tyre undoubtedly had a significant mainland presence under king Hiram, who reigned in the 10th century BC,[38] centuries before the prophet Ezekiel lived.

Here we have multiple references from various sources rooted in the same sociohistorical context as Ezekiel, several of which originated centuries earlier, which identify this same mainland city as “Tyre.” This removes any possibly remaining shred of doubt that the mainland settlement was something separate and distinguishable from Tyre, especially in the minds of the Israelites of that era.

Furthermore, as we have already seen, these references mention that Old Tyre on the mainland was heavily fortified.[27,28,30-32] There would have been plenty of “walls and towers” for Nebuchadnezzar’s armies to demolish, another detail of this prophecy which has been called in to question by skeptics. In fact, the ruins of this city will come in to play a few hundred years later.

ALEXANDER THE GREAT CONQUERS TYRE

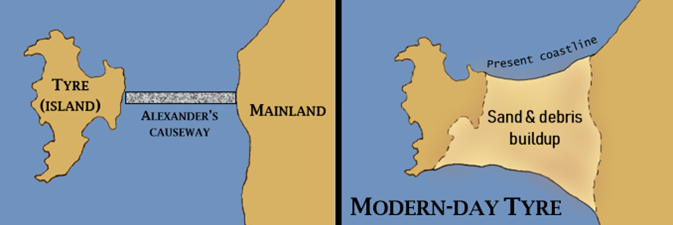

About 250 years after Nebuchadnezzar’s siege, the next “wave” crashed against Tyre in the form of Alexander the Great. In his famous conquest of the Achaemenid-Persian empire, Alexander and his Macedonian armies reached Tyre in ~332 BC. Unlike the other cities that Alexander encountered on his route to Egypt, Tyre refused to capitulate. They killed Alexander’s messengers and holed up behind the walls of their island-city fortress.[40,41] The Tyrians evidently had complete confidence in their defenses; the fortress walls were 150-feet high, and the kilometer-wide strait separating the island from the mainland was over 20 feet deep.[39] But although these defenses were indeed formidable, they had underestimated Alexander’s creativity and audacity.

Rather than simply leaving behind a garrison to contain the island and continue on with his campaign, Alexander did what initially seemed ludicrous to both his men and the Tyrians; he decided to construct a mole through the sea to the island to allow his armies to cross the strait and attack the island-fortress by foot.[39,40] He began by dismantling what was left of Old Tyre and submerging the resulting rubble, rock, and debris into the sea to serve as a foundation for his causeway to the island-city.[39,40] His men fetched timber, dirt, and sand to use as additional building materials for this mole.[39,40] After seven months of grueling physical labor, all while fending off enemy naval sorties, the construction of the kilometer-long causeway through the sea was finally completed and Alexander launched a successful attack on the island, breaching the fortress walls and destroying most of the city.[40]

It is at this point that we begin to see certain details of Ezekiel’s prophecy in a new light. The statements in verses 4 (“[The LORD] will scrape [Tyre’s] dust from her”) and 12 (“they will lay your stones, your timber, and your soil in the midst of the water”) likely seemed wildly improbable to Ezekiel’s contemporaries – why would any attacking force take the time and effort to throw the stones, timber, and soil of a city in to the sea? Yet with the benefit of hindsight, we see that this was no mere exaggeration or colorful language to portray Tyre’s ruin in a poetic manner; rather, these details were fulfilled in a most literal, albeit bizarre fashion.

As a result of this remarkable engineering feat, the Mediterranean coastline has been permanently altered. In the ensuing centuries, sand and other debris gradually accumulated around and on top of Alexander’s mole.[39] This steady buildup has resulted in a permanent land-bridge connecting the island to the mainland. What once was an offshore island is now a peninsula jutting out into the sea, with Alexander’s mole at its base.*

*Alexander’s mole in combination with several earthquakes caused changes to the sea level of the area and parts of the ancient city now lie beneath the sea (see verse 19).[49,5,54]

MORE “WAVES” OF NATIONS

Along with Tyre, Alexander the Great conquered each of the Phoenician city-states in the Levant.* The Phoenician people as a whole were either killed or assimilated into other peoples and cultures, marking the end of Phoenician civilization.[40] But although Tyre’s mainland and island settlements had now been completely devastated, its coastline permanently altered, and its people dissolved, Tyre had not seen its last day. As a strategic and important port city, the Greeks quickly rebuilt Tyre and it wasn’t long until it regained its former prominence and notoriety.[21] Clearly, Ezekiel’s prediction that Tyre would never be rebuilt had not yet come to pass. But Nebuchadnezzar and Alexander were only the beginning.

Over the next ~1,500 years, many more such “waves” of nations would invade or attempt to colonize Tyre, and the city would change hands countless times. First came the different Hellenistic empires – the Seleucid, Ptolemaic, and the Antigonid dynasties – who fought over Tyre in the Wars of the Diadochi following the death of Alexander the Great.[43,40] Then came the Romans, followed by the Byzantines, the Sassanids, the early Islamic Caliphates (Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, etc.), the Seljuk Turks, the Fatimids, the Christian Crusaders, and the Ayyubids, just to name a few.[4,11,44] Tyre withstood five major sieges during this time, each resulting in varying degrees of damage to the city.[45] Finally, in 1291, Tyre suffered a fatal blow.

*After learning the details of Tyre’s defeat, the other coastal cities along Alexander’s direct route south to Egypt immediately submitted to him.[39,40,51] This is likely what Ezekiel is referring to in verses 15-18 (Ezek. 26:15-18).

TYRE’S ULTIMATE END

In the late 1200’s, the Egyptian Mamluks launched what would be a successful campaign to expel the Christian Crusaders from the Levant. By this time, the Crusaders controlled only a few coastal outposts, one of which was Tyre. In 1291, Acre, the last major Crusader stronghold in the region, fell to the Mamluks.[46] Knowing they would soon meet the same fate as those at Acre, the Frankish Crusaders who held Tyre abandoned the city.[47] The Mamluks reached Tyre shortly thereafter and found it deserted, and, to prevent the Crusader armies from re-occupying Tyre, they completely leveled the entire city.[48,11] Tyre had at last reached its end; it had been reduced to rubble and would never be rebuilt (see Ezek. 26:14). The renowned city of antiquity sank into obscurity.

There are numerous accounts of travelers visiting the deserted site of Tyre in the centuries that followed and reporting that the once-great city was nothing more than a heap of ruins, with a “few” inhabitants who subsisted upon fishing (see Ezek. 26:5, 26:14).[43,47,44] At long last, we see the culminating event of Tyre’s downfall more than 2,000 years after it was foretold by Ezekiel. The thorough destruction of Tyre at the hands of the Mamluks marks the final affair in the cascade of events which collectively satisfy this prophecy in its entirety.

THE MODERN CITY OF TYRE

The fact that there is a city by the name of Tyre in Lebanon today seems to contradict Ezekiel’s declaration that the city would “never be rebuilt” (Ezek. 26:14). However, the existence of modern-day Tyre in no way refutes Ezekiel 26:14. As we will see, modern Tyre shares nothing but a name with its predecessor.

After its destruction at the hands of the Mamluks in 1291, Tyre lay in utter ruin and desolation for almost 500 years.[43,44] The site of the ancient city sat virtually untouched until around 1750 when the first of several minor construction projects began there.[44] However, each of these was short-lived; the Levant would be at the center of near-constant conflict and turmoil which has continued through the present, severely limiting the development of the region. Today, Tyre exists as a small and relatively insignificant city in Lebanon. Unlike the economy that characterized Tyre’s past greatness, modern-day Tyre relies primarily on tourism.[49] Tyre’s once-famed harbor is now the smallest in all of Lebanon and its usage is limited to fishing and leisure activities.[49]

It’s also worth noting that by the time modern Tyre was settled, the Phoenician people had long since been assimilated into other cultures, people groups, and nations; this began about 2,000 years prior with the Hellenization of the region following Alexander the Great’s conquest, and continued throughout the Islamic age with the Islamization and Arabization of the region.[43,40]

I need hardly state the obvious: modern-day Tyre is a fundamentally different city from the mighty Phoenician city-state.

CONCLUSION

It is no brilliant prediction that Tyre would eventually be overcome in the course of history; given enough time, all nation-states eventually fall. What is so compelling about the case of Tyre is the bizarre and unlikely manner in which events unfolded to bring about its destruction in a means which strikingly matches the prediction of Ezekiel. The details of Tyre’s downfall likely seemed wildly improbable to Ezekiel’s contemporaries, yet with the perspective afforded to us by hindsight, we see how the peculiar details of this prophecy materialized in the most unexpected of ways.

As we frequently encounter when engaging with the Bible, the scope and timeframe in which God operates often far exceeds the purview of individuals. With our short lifespans, limited perspectives, and shortsighted nature, it is not always easy or even possible to discern how God is moving and working in the world. But when you look back through the corridors of time, God’s handiwork becomes plain and obvious.

What other Biblical truths, whether on a grand scale or in your own personal life, are playing out right before your eyes, but in a manner so gradual, unobtrusive, or unexpected that it is difficult to recognize?

P.S.

As always when we are investigating historical matters in the distant past, we would be wise to practice humility and recognize the fact that we do not have a complete picture of events or circumstances. The vast majority of historical sources do not survive; they are destroyed or lost beneath the sands of time, and as a result our understanding of events is often skewed and incomplete. In light of this, it is important to recognize that history is often provisional. We need to be open to the possibility that alternate sources may be uncovered in the future that may clarify, deviate from, or even negate our current understanding of historical events.*

This, combined with the fact that we are attempting to analyze events which involve people whose culture, mindsets and worldviews are drastically different from our own should keep us honest!

*To illustrate this point, for many years the academic community questioned whether Nebuchadnezzar ever besieged Tyre, and many dismissed the prophecy in Ezekiel 26 as a massive failure. However, the discovery of Babylonian cuneiform tablets in 1926, known as the Unger tablets, confirmed the historicity of Nebuchadnezzar’s siege.[50]

Another example of this is the confirmation of the existence of the Babylonian ruler by the name of Belshazzar who ruled as king regent in place of his father Nabonidus (see Daniel chapter 5).[52,53] Prior to the finding of the Nabonidus Chronicle in the late 1800’s, there was no record of a Babylonian “king” by the name of Belshazzar, leading scholars to dismiss the account in Daniel 5 as fiction.

REFERENCES

- Ezekiel 26 :: New king James version (NKJV) [Internet]. Blue Letter Bible. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.blueletterbible.org/nkjv/eze/26/1/p1/s_828001

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Tyre. In: Encyclopedia Britannica. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Tyre

- Mark JJ. Tyre. World History Encyclopedia [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 16]; Available from: https://www.worldhistory.org/Tyre/

- Ancient Tyre [Internet]. World Monuments Fund. 2018 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.wmf.org/project/ancient-tyre

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Tyre [Internet]. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/299/

- Tyre [Internet]. Middleeast.com. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: http://www.middleeast.com/tyre.htm

- TimeTravelRome. Alexander the great’s spectacular Siege of Tyre [Internet]. Time Travel Rome. 2019 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.timetravelrome.com/2019/05/02/alexander-greats-spectacular-siege-tyre/

- Wikipedia contributors. Ushu [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ushu

- Dutt SC. Historical studies and recreations. London, England: Trübner; 1879

- Bikai P. The Land of Tyre, found in John A. Bloom’s essay “Is Fulfilled Prophecy of Value for Scholarly Apologetics?” In: 47th annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society [Internet]. La Mirada, CA: Biola University; 1995 [cited 2023 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.globaljournalct.com/is-fulfilled-prophecy-of-value-for-scholarly-apologetics/

- Lendering J. Tyre [Internet]. Livius.org. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.livius.org/articles/place/tyre/

- Fleming, WB. The History of Tyre. Columbia University Press; 1915. p.46.

- Solomon M, Billings B. Hope of the World. The BEMA Podcast: episode 94 [Internet]. Moscow, ID: BEMA Discipleship; 2018. 12m:45s [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.bemadiscipleship.com/94?t=766

- Solomon M, Billings B. Crossroads of the Earth. The BEMA Podcast: episode 35 [Internet]. Moscow, ID: BEMA Discipleship; 2017. 23m:08s [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.bemadiscipleship.com/35?t=1388

- Solomon, M. Covered in his dust [Internet]. MakingTalmidim.Blogspot.com. 2016 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://makingtalmidim.blogspot.com/2016/09/2-john-woman.html

- Hopkins IWJ. The ‘daughters of Judah’ are really rural satellites of an urban center [Internet]. The BAS Library. 2015 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/6/5/4

- Mueller J. Ancient Walls. Kapheira Press; 2015 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://bible-history.com/linkpage/ancient-walls

- Smith, W. Meaning and Definition for ‘daughter’ in Smiths Bible Dictionary [Internet]. Bible-history.com. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://bible-history.com/smiths/d/daughter

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Biblical literature – Ezekiel. In: Encyclopedia Britannica. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/biblical-literature/Ezekiel

- What happened to Tyre? [Internet]. Bible Reading Archeology. 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblereadingarcheology.com/2017/09/13/what-happened-to-tyre/

- Ezekiel 26:1-14: A proof text for inerrancy of old testament – associates for biblical research [Internet]. Biblearchaeology.org. 2006 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblearchaeology.org/research/divided-kingdom/3304-ezekiel-26114-a-proof-text-for-inerrancy-or-fallibility-of-the-old-testament

- QS World University Rankings for Classics & Ancient History 2021 [Internet]. Top Universities. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2021/classics-ancient-history

- Rome’s La Sapienza rated top university in the world for Classics [Internet]. Wanted in Rome. 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.wantedinrome.com/news/romes-la-sapienza-rated-top-university-in-the-world-for-classics.html

- Wikipedia contributors. Sabatino Moscati [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://it.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sabatino_Moscati&oldid=130745789

- Moscati S, editor. The Phoenicians: Under the scientific direction of Sabatino moscati by Sabatino moscati New York, NY: Abbeville Press; 1988. p.140-151. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.mullenbooks.com/pages/books/128629/sabatino-moscati/the-phoenicians-under-the-scientific-direction-of-sabatino-moscati

- Brown, F, Driver, S.R., Briggs, C. H6865 – ṣōr – Strong’s Hebrew lexicon (kjv) [Internet]. Blue Letter Bible. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h6865/kjv/wlc/0-1/

- Brown, F, Driver, S.R., Briggs, C. A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1907. p.131, 862 – 863. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/bookstore/resources/brown-driver-briggs.pdf

- Brown, F, Driver, S.R., Briggs, C. The Enhanced BROWN-DRIVER-BRIGGS Hebrew and English Lexicon. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1907. p.374, 2095. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https:/hebrewcollege.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/BDB.pdf

- Joshua 19. Cambridge bible for schools and colleges [Internet]. Biblehub.com. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/cambridge/joshua/19.htm

- Spence-Jones, Maurice, H. D. (editor). Joshua 19. The Pulpit Commentary [internet]. Biblehub.com. 1883. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/2_samuel/24.htm

- Joshua 19. Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary [Internet]. Biblehub.com. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/jfb/joshua/19.htm

- Bement RB. Tyre; The history of Phoenicia, Palestine and Syria, and the final captivity of Israel and Judah by the Assyrians. General Books; 2012. p.64 – 67.

- Joshua 19. Keil and Delitzsch OT commentary [Internet]. Biblehub.com. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/kad/joshua/19.htm

- 2 Samuel 24. Cambridge bible for schools and colleges [Internet]. Biblehub.com. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/cambridge/2_samuel/24.htm

- Spence-Jones, Maurice, H. D. (editor). 2 Samuel 24. The Pulpit Commentary [internet]. Biblehub.com. 1883. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/2_samuel/24.htm

- Wikipedia contributors. Mount Lebanon [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Lebanon

- Wikipedia contributors. Cedars of God [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cedars_of_God

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Hiram. In: Encyclopedia Britannica. 2012 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hiram-king-of-Tyre

- Green P. Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B.C: A historical biography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1992. p.247-265.

- Mark JJ. Phoenicia. World History Encyclopedia [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Jan 16]; Available from: https://www.worldhistory.org/phoenicia/

- Tyre-aerial-photo-by-France-military-1934 [Internet]. Wikimedia.org. 2021 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tyre-aerial-photo-by-France-Military-1934.jpg

- Google Maps. Tyre, Lebanon [Internet]. Google; 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Tyre,+Lebanon

- Jidejian, N. TYRE Through The Ages. Beirut: Dar El-Mashreq Publishers; 1969. p.19-37, 119-141, 265, 272

- Wikipedia contributors. History of Tyre, Lebanon [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Tyre,_Lebanon

- Wikipedia contributors. Siege of Tyre [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Tyre

- Wikipedia contributors. Siege of Acre (1291) [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Tyre

- Walcott Reddit, M.Antiquities of the Orient Unveiled. New York: Temple Publishing Union; 1875. p.145, 154. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from https://www.google.com/books/edition/Antiquities_of_the_Orient_Unveiled/GUeBAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA13&printsec=frontcover

- Harris W. Lebanon: A History, 600-2011. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. p.67. Available from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lebanon/q_xoAgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA4&printsec=frontcover

- UN Habitat Lebanon, United Nations Human Settlement Program. Tyre City Profile 2017 [Internet]. 2017. p.59-60. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/TyreCP2017.pdf

- Wikipedia contributors. Siege of Tyre (586-573 BC) [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2023. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Tyre_(586%E2%80%93573_BC)

- Wikipedia contributors. Alexander the Great [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2023. [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great

- Wikipedia contributors. Nabonidus Chronicle [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nabonidus_Chronicle

- Shea W. Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: An Update [Internet]. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Andrews University Press; 1982. Andrews University Seminary Studies, v. 20, no. 2. p.133-149. [cited 2023 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.andrews.edu/library/car/cardigital/Periodicals/AUSS/1982-2/1982-2-05.pdf

- Lendering J. Tyre [Internet]. Livius.org. 2018 [cited 2023 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.livius.org/articles/place/tyre/tyre-photos/tyre-city-egyptian-harbor

- NASA InternationalSpaceStation TyreSurLebanon01032003 ISS006-E-31938 [Internet]. Wikimedia.org. 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NASA_InternationalSpaceStation_TyreSurLebanon01032003_ISS006-E-31938.jpg